| Home |

| Early Life |

| Maps |

| Oregon Laws |

| The Trail |

| Bush Biography |

| Tumwater Born |

| Thurston County |

| State History |

| Bush Farm Today |

| FAQs |

| Timeline |

Fighting the Indians in 1855

|

| Also in this vicinity seven white men on their way from Camp Naches to Fort Steilacoom were ambushed by Indians October 31, 1855 Two of those killed were Colonel A. Benton Moses and Lt. Colonel Joseph Miles. | |||||||||

| History

of the Pacific Northwest - Oregon and

Washington Volume I - 1889 Page 540 Before passing to the narrative of events, a recurrence to the condition of the territory becomes interesting. The hitherto uniform and peaceful character of the Indians, the contempt or pity indulged the fact that they had so recently and so cordially entered into the treaties, ceding their title to the lands with the accompanying pledge that they would live in friendship with the Whites, had created the feeling of perfect security in our recognized superiority; and the idea was contemplated that there could by any possibility be any cause of dread or apprehension from such an enemy. The territory was illy supplied with arms and ammunition. The necessary supplies to maintain either offensive or defensive war were almost entirely lacking. Such weapons as had been in the country had been carried off by the miners; and, without a thought that they would be so soon required, but few had refurnished themselves. On hearing the news from the Yakima county, on being apprised of the real danger which surrounded the settlements, and in fact within our very midst, the reaction at once carried the people to the other extreme; - the situation amounted almost to a "stampede." Too late to prevent its first unfortunate consequences, the fact was apparent that an Indian war existed; that we had to combat an enemy whose power to inflict injury was not to be despised, who had to be chastised, who had to be taught submission. The company of volunteers enrolled at Olympia, in response to Governor Mason's proclamation (Company A), elected Gilmore Hays, Captain, Jared S. Hurd, First Lieutenant, and William Martin, second Lieutenant. That company reported to Captain Maurice Maloney, Fourth Infantry, U.S. Army, in command at Fort Steilacoom, on Saturday, October 20th. On Sunday, the twenty-first, Company A, Washington Territory Volunteers, started for the Yakima country via the Naches Pass. Lieutenant Slaughter, Captain of Eaton's Company of Rangers with forty United States regulars, was encamped on White river prairie where, upon the twenty-first, he had been joined by Captain Maloney with seventy-five United States infantry. They remained there until the twenty-fourth, at which time, captain Hay's company of volunteers having come up, the expedition, under command of Captain Maloney, U.S. Army, marched to the Naches river, which they reached on the 28th of October. At that point, captain Maloney remained to recruit the animals. He sent in an express to Lieutenant Nugen, U.S. Army, in command at Fort Steilacoom, that the delay in the march of the troops from Fort Vancouver, the reliably reported heavy force of the hostile Indians in front, the alarming character of the reports in the rear as to the disaffection of the Puget Sound Indians, and the actual outbreak of many since the troops had left Fort Steilacoom, had occasioned him (Captain Maloney) to determine upon returning with his command to the west of the mountains to protect the Puget Sound settlements. The express party to Lieutenant Nugen consisted of A. Benton Moses, Joseph Miles, George R. Bright, Dr. Matthew P. Burns, Antonio B. Rabbeson and William Tidd. On Wednesday, October 31st, the party were fired upon from an ambush near White river; and Messrs. Moses and Miles were instantly killed. Upon the recovery of their bodies they were found shockingly mutilated. After severe suffering and hardships, the surviving members of the party succeeded in reaching the settlements. Equal promptness had been displayed in raising the second company of volunteers, ordered by Acting Governor Mason's proclamation to report to Major Rains, U.S. Army, at Fort Vancouver. That company (Company B) elected William Strong (late Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of Oregon), captain. A company of volunteers, commanded by Captain Robert Newell, consisting of trappers and others well acquainted with the country, had been raised about the same time for scouting purposes in the vicinity of Fort Vancouver, and had been accepted into the service of the United States. Upon the withdrawal of the troops from Fort Vancouver, the citizens organized a company of fifty men at Vancouver for home defense, of which William Kelly was elected captain. The threatening condition of affairs on Puget Sound foreshadowed by Captain Maloney's dispatch to Lieutenant Nugen had been full realized. No sooner had the force under Captain Maloney left Fort Steilacoom for the Yakima country, than the Indians west of the mountains evinced unmistakable evidence that they were disaffected, that they were well apprised of the movements of the hostile Yakimas, and in close communication with them. those facts prompted Acting Governor Mason, on the 19th of October, to authorize Captain Charles H. Eaton to raise a company of rangers. The conduct of Leschi and Quiemuth and their bands of disaffected Nisquallys had rendered necessary such action. The company was fully organized (forty-one strong), elected him captain, James McAllister, James Tullis and Alonzo M. Poe lieutenants, and took the field on the 24th of October. Captain Eaton had come to Oregon in 1843, and was thoroughly acquainted with the country and with the Indians. No wiser selection, considering the peculiar duties imposed, could have been made. James McAllister, First Lieutenant, was an old citizen and pioneer of Thurston county (1844). Captain Eaton was instructed to divide his company into three parties and scour the whole country along the western base of the Cascade Mountains between the Snoqualmie Pass and the Lewis River Pass of the Cascades, and intercept communication between the Indians west of the Cascades and the Indians east. He was especially enjoined to notify all Indians found upon the line of march to remove west to the shores of Puget Sound; and upon their willingness or refusal so to remove was to be determined their friendly or hostile disposition. On the 28th of October, Captain Eaton having received news that Leschi, with a large party of Indians, were fishing twelve miles distant on the White river, at the crossing by the military road from Fort Steilacoom to Fort Walla Walla, Lieutenant James McAllister applied for permission to make a friendly visit to them, which was granted. He was accompanied by Mr. Connell and two friendly Indians. The whole party were treacherously killed by a band of the hostiles led by Quiemuth long before reaching Leschi's camp. About an hour after Lieutenant McAllister had left camp, Captain Eaton, accompanied by James W. Wiley , made a reconnaissance of a slough lying ahead about three-quarters of a mile, which had been passed to White river. Upon returning, and before they had reached the house which his small command (now reduced to eleven) occupied, several shots had been fired by the hostiles. Captain Eaton at once abandoned the house (that of Charles Baden, and built of thin cedar boards), and fell back to an Indian log cabin, in which had been stored a quantity of oats, wheat, peas, salmon skins and berries. A log Indian barn looking to the eastward was demolished to insure safety; and the cabin was additionally fortified, as far as practicable. The baggage was transferred from Baden's house. The horses were picketed about two hundred yards to the northward of the cabin, and a water cask brought from the house and filled. At sundown the Indians attacked the cabin in force, and kept up a constant fire until after two o'clock, and at intervals thereafter during the remainder of the night. The horses of the command were all stolen by the Indians. On the next morning, Captain Eaton strengthened his position. At eleven o'clock, an express from Fort Steilacoom, to Captain Maloney's camp, three in number, came into the fortification. Eaton's gallant little band maintained their position for one hundred and one hours without losing a man, and then effected their escape to Steilacoom. It is not known what was the loss of the enemy. Indian testimony, however, has fixed the number of Indians killed at seven. |

|||||||||

| James

McAllister, Michael Connell and

the Start of the Indian War Submitted by Gary

Reese

From usgennet.org

letter by JAMES McALLISTER Nisqually Bottoms, Washington Territory. 16 October 1855 To Superintendent of Indian Affairs, Washington Territory. Dear Sir: From the most reliable Indians that we have in this country, we have information and are satisfied that Leschi, a sub-chief and half Clickitat is and has been doing all that he could possibly do to unite the Indians of this country to raise against the whites in a hostile manner and has had some join in with him already. Sir, I am of the opinion that he should be attended to as soon as convenient for fear that he might do something bad. Let his arrangements be stopped at once. Your attention to the above will be exceedingly appreciated by the people of Nisqually Bottoms. For further information, call, and I am at your service. Clarence Bagley, History of King County. Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1929 p. 164-65. (Some) temporary successes led those narrow visioned Red Men to believe that the time was ripe for making a clean-up of white settlements and ridding their illahee of the avaricious and obnoxious Boston man. Meanwhile the few scattered settlers on the White River and contiguous territory were living quietly without a thought that trouble was brewing or danger impending. They were doomed to a sad awakening. The trouble was precipitated by the organization of what was known as the Eaton Rangers, a company organized with Charles Eaton as captain, and James McAllister as lieutenant. This company, nineteen strong, started with instructions to apprehend Leschi and his brother, Quiemuth, at their home and bring them to Olympia to be under government surveillance; it having been reported that they had been for some time preparing their band for active hostilities against the settlements. The brothers having learned of the purpose for which the company was organized left (the Nisqually Valley) hurriedly; Quiemuth leaving the plow, which he was following in the unfinished furrow. Finding the Indians had gone, Captain Eaton spent a couple of days reconnoitering on the upper Puyallup, and then sent Lieutenant James McAllister with a small party to make a reconnaissance in the vicinity of White River. McAllister was accompanied by a man named (Michael) Connell who had a claim on White River. Both were shot from ambush on the road leading from the prairie through a swampy tract with fallen timber and thick underbrush on either side. This happened on the 27th of October; and was the first overt act of hostilities on the west of the Cascade Range. The following day, October 28, 1855, the Indians raided the White River settlement, ruthlessly butchering men, women, and children, nine in all. Four children were saved from the slaughter, three from the Jones household who were taken to Seattle by a friendly Indian, and placed on board the Decatur for protection; and one, George King, who was taken by the Indians and held until the following spring, when he was delivered to the military authorities at Fort Steilacoom." (The adventures of the Jones children are reported on pages 165-72 of Clarence Bagley's book as well as details of the massacre.). Edward Huggins, "Letter to Eva Emory Dye, May 27, 1904 regarding James McAllister" I was well acquainted with James McAllister. He frequently was at the fort. He was in appearance, a regular Missourian, or what I supposed a Missourian to look like. He was about six feet in height, rather thin, but muscular. He was a good hunter, and towards the end of our wild cattle business, and when cattle became so wild, that they required to be hunted like deer, McAllister was paid, by the company five dollars, for every wild animal he killed, and he didn't get rich at the business, I assure you. Mrs. Hartman was the woman who obtained the ledger prize for the best story about early happenings, was one of McAllisters daughters. He had several other children. One of the daughters married Joe Bunting, the man suspected of being at the head of the party who broke into Governor Stevens' outer office and killed the brother of Leschi, Quiemulth, who was supposed to be carefully guarded by another Missourian, I think. James McAllister was of limited education, hardly any, if I be not mistaken. Was a quiet man, had very little to say upon any subject. I suppose you saw Mrs. Hartman's (Sarah McAllister) prize story. I thought it 'twas a wretched effusion, full of untruths and exaggerations. In it she say's that her father was made an Indian, and joined in the councils of the Indians. What gammon! I never heard of the Nisqually Indians meeting in council. About Simmons. I can't add but little to what I've already said about him. I always thought 'twas very unfair to give a man, without any education, position of great trust and grave importance to the public. He was superintendent of Indian Affairs at the most critical period of the early history of this country, and had to depend entirely upon the integrity of aids to preform his duties, and 'twas well known that some of his assistants were men who would bear watching. One of his principal aids was a man dubbed Major Goldsboro a brother of the U.S.Admiral of that name. He was a fine looking man, honest for all I know to the contrary. He was a man of superior education. Was on very friendly terms with the officers at Fort Steilacoom. He left Puget Sound just after the end of the Indian War of 1855-56, got a place in the government office in Washington, and, I think, remained there all his life. At the time Simmons was at the head of the Indian department in Washington Territory. The Indians were receiving very large payments, annually, always, I think, in goods, and report said that the Indian Agent made a large income from commissions paid by parties contracting to furnish the goods to the department. Of course don't know anything about this, and can't vouch for the truth of the report, but 'twas believed to be true by a large number of people. Simmons was another of the McAllister type of men, large, big boned and strong. He often came to our fort and always lodged in my cabin, and I've listened with interest to many a story told by him of his many adventures. His lack of education must have been a severe handicap to him. JAMES McALLISTER Ezra Meeker, "James McAllister, " Pioneer Reminiscences of Puget Sound. Seattle: Lowman and Hanford, 1903, p. 535-36. James McAllister was the first to take a claim away from the prairies near Deschutes. He was, also, among the first to be killed by the Indians in the war of 1855-6. With the consent of the Indians, he took his claim in the Nisqually bottom, not far from the council ground of the tribe of that name. Mrs. Hartman, daughter of James McAllister wrote several years ago a long article from which are selected the following paragraphs: "We had all kinds of game, which was more plentiful than the tame stack now, fish and clams, dried and fresh, the Indians shaking us how to prepare them, but we never succeeded in learning the art of drying them. We were successful in drying fruits, the Indians' mode requiring no sugar. "For vegetables we had lackamas, speacotes, and numerous other roots. We children learned to like the Indian food so well that we thought we could not exist without it. We kept a supply as long as we could get it, but I have not seen any for many years. "In 1846, mother disliking to stay alone while father was building, he laughingly told her he had seen two big stumps side by side, and that if she would live in them he would take her with him. Mother told him she would go, so father scraped out the stumps and made a roof, and mother moved in with her six children. "She found it very comfortable, the burnt out roots making such nice cubbyholes for stowing away things. Mother continued to live in her stump house until father built a house, the work being necessarily slow, for father had but few tools." To one familiar with the big cedar stumps of Nisqually bottom, this charming little story will not seem improbable. This home was not far from Nisqually, and one day Mrs. McAllister went to see Mrs. Huggins, and at that time gave an account of the hardships of the trip to the Sound. They grew short of provisions so that the children were crying from hunger, somewhere on the Cowlitz trail, between the Company's store near the mouth of that stream where Monticello afterward stood and the Cowlitz Farm. Here Mr. John Work, father of Mrs. Huggins, met them on his way to Fort Vancouver from Fort Simpson, away up on the Northwest Coast, where he had an important post. Mr. Work was a tender-hearted man and appreciated the pitiful condition of the poor mother and her children. He promptly unloaded his packhorse and gave Mrs. McAllister all that was left of the plentiful supply of provisions he had secured at Nisqually, enough to last them until they could reach the Company's farm at Cowlitz. This kindness Mrs. McAllister had not forgotten, and showed much pleasure in telling of it to his daughter. Somebody put a story afloat a few years ago that it was the noted Indian Leschi who had performed this generous deed. McALLISTER, JAMES Cordelia Hawk Putvin "About Indians," Stories of the Pioneers. True stories from members of the Daughters of the Pioneers of Washington. Daughters of the Pioneers, 1986, p. 20-22. My grandfather, James McAllister, my grandmother Charlotte, and their family, left Kentucky for Missouri during the latter part of the year 1843, so that they could get an early start for the Oregon Country in the spring of 1844. Their daughter became ill during the journey, so they were happy to reach Whitman's Mission where the doctor could treat her illness. His wife, Narcissa, also showed them all possible kindness. But they had planned on going to the Puget Sound country, so when the girl was well enough to travel, they and four other families made their way down the Columbia River as far as Sophies Island (Washougal), where winter overtook them and they made camp. In the spring they continued down the Columbia as far as the mouth of the Cowlitz River, and followed that stream north. While camped along the Cowlitz one day they had their first encounter with Indians. The men were all off on a hunting trip, and the women and children were alone, when a roving band of Indians came by. Seeing no men around, they began helping themselves to the bright colored patchwork quilts and other useful articles in the camp. The Indians had nothing but contempt for their white skinned brothers, thinking them weak and undernourished. The Indians only turned pale when they were sick; these people were pale all the time, therefore they must be a weak, sickly race. So they were quite surprised when Charlotte, who came from Kentucky fighting stock and could not bear to see her hard earned possessions being carried away, pulled up a tent pole and laid it about right and left over the Indians' heads, shoulders and backs until she put them to flight. The next day the old chief returned and offered grandfather $500 for the "white squaw", but grandfather soon gave him to understand that white men did not sell their wives. The great chief Synatco's oldest son, Leschi, had heard of their coming and met them near here. He was eager to see the "white squaws", as there were no other white women in the territory at this time. There had been three at Whitman's Mission, and there were four white women and one colored in their group, only eight non-Indian women in the whole of Washington Territory. Leschi told them they were welcome to make their homes on any of their tribe's property, which included most of the Puget Sound area. After trying a couple of other places, they finally discovered the Nisqually Valley, and took out a claim there at the junction of Skonadaub and Squaquid creeks (later Medicine and McAllister). The farm was on part of the Indian Council Grounds, but was gladly relinquished by them. This place was about 15 miles from where they had been living. Grandfather had to stay on the new place while he cleared the land and prepared to build living quarters for them. Grandmother did not like this arrangement in which she had to be alone so much of the time with several small children, and she kept after him to find a place for them to live. Grandfather laughingly told her he had seen two hollow stumps nearby that she could move into. She took him seriously and would not be satisfied until he had promised to put roofs on them and clean them out. This he did, and along with a tent, the family of eight lived very comfortably until a house was prepared for them. The land was cleared and proved to be very fertile; vegetables grew to a wondrous size, potatoes weighing eight to ten pounds were not uncommon, and they could grow three crops of wheat in a summer. They planted an orchard, and with all the wild berries in the woods they soon became quite prosperous. Grandmother took in three Indian girls to train as servants, as well as a boy, Clifwhalen. She found them quick to learn, willing to work, honest and loyal. So they lived and prospered among the Indians as brothers for many years. Then other white people began moving in who were not friendly with the Indians, but regarded them as savages rather than human beings, and treated them as such. Many incidents happened which made the Indians unhappy and distrustful of the white man. But what finally put the Indians on the warpath involved the daughter of Synatco. She had been married to a white soldier in an Indian ceremony. When he was transferred to another fort, where he could not take a wife, he told her that they were not legally married, and sent her back to her father. The chief, Synatco, was heartbroken. He fell to the ground and crept, refusing to walk upright any more. He howled and howled, which meant he was debased lower than a dog. Her brothers also were outraged, and swore to kill all the white men, except the older settlers who had joined the tribe. Synatco now abdicated in favor of his oldest son, Leschi, and died soon after. Leschi too had been heartbroken by the treatment his sister had received. However, he did not want to declare war against the whites, many of whom were his friends, so he took some of his braves and moved up into the mountains, where they barricaded themselves until the Indians quieted down. But this time the Indians did not quiet down. Many hostiles from the north moved in, and with war paint and much noise, put on many demonstrations and dances. Knowing the strong friendship between Leschi and my grandfather the white people appealed to him to carry a peace commission to him to sign. They knew if anyone could reach Leschi it was grandfather. He was offered and accepted a commission as First Lieutenant in the Puget Sound Volunteers, and with a group of other volunteers and Leschi's brother, Stoki, to guide them, they started off. After they had gone, grandmother became uneasy and sent Clifwhalen, the Indian boy they had raised, and George, her oldest son, to follow him. She told Clifwhalen that when they caught up with him he should stay by his side night and day, and see that no harm came to him. Clifwhalen said, "I will follow him as his shadow and only death will keep me from it." Grandmother knew that he would keep his promise, which he did. When the boys caught up with the party two days later, and Clifwhalen found that Stoki was their guide, he tried to warn grandfather that Stoki was a traitor and would lead them into a trap. But grandfather had always trusted the Indians, and thought that Clifwhalen was mistaken. What did a boy his age know about these things, anyway! So that evening they started out to find Leschi -- grandfather, Lt. Connell, Stoki as guide and Clifwhalen as servant. The Indians had a clever way of laying an ambush. They had two squads of their warriors in the woods beside the trail about a mile and a half apart. So grandfather and his group passed the first squad without any suspicion, only to have the second squad come running out of the woods shooting, and with the first party coming up behind, they hadn't a chance. Clifwhalen shouted to grandfather to take to the woods, but apparently he did not hear him, and he was the first one killed. Clifwhalen managed to escape with some bullet holes in his clothing. The men left at the camp heard the shooting and went to investigate only to be met by the Indians, but managed to get back to their camp with only one loss. George was sent back to the fort to warn the people at home of what had happened, and to send help. He also managed to get through safely. The boys arrived home only to find the family being held prisoners in the house, which was surrounded by Indians. Their imprisonment and eventual escape to Fort Nisqually, where they stayed until hostilities ceased, is another story. Grandfather's body was located and brought to the Fort for burial, and was later moved to the cemetery at Tumwater. |

|||||||||

| James

McAllister From Tumwater Masonic Cemetery web site Among the pioneers accompanying Michael T. Simmons to Tumwater in 1845 was James McAllister with his wife and children. He was born in Kentucky, but like the other settlers, had embarked on the Oregon Trail from Missouri. McAllister did not stay in Tumwater long. He moved to the Nisqually Valley, where he made his claim. McAllister Creek and McAllister Springs are named after him. When the Indian War broke out in 1855, James McAllister volunteered to join the Puget Sound Rangers, commanded by Capt. Charles Eaton. On the 22nd of October, 1855 at the house of Nathan Eaton on the Yelm Highway, McAllister was elected lieutenant. Right after his election, the company of 19 men departed for the Puyallup River to find Chief Leschi. Not finding any Indians, the group continued on. Lt. McAllister requested permission to reconnoiter the military road leading towards the White River. He took with him a resident of the area, Mr. Connell, and 2 Indians. Eaton told him to return that evening. McAllister replied, "I will return if I am alive." He never returned. The sharp report of a rifle alerted his company to his fate. His body was found a few days later not far from the smoking ruins of Connell's house. It was taken to the fort on Chambers' prairie where his family had taken refuge. The funeral took place November 11. "It rained incessantly all day yet the torrents which fell did not abate the desire to render every respect to his memory." He was survived by his wife, Charlotte. They had been married in 1834 and had had 10 children, the youngest of which was just 2 years old when her father was killed. Charlotte McAllister remarried William Mengel. They lost an infant son in 1859. All 3 Mengels lie in this same site. The McAllisters' oldest daughter, America, married Thomas Chambers of the large Chambers family who settled on Chambers Prairie. Daughter Mary Jane married David Hartman. The Hartmans were prominent residents of Nisqually. The youngest daughter, Elizabeth, married Isaac Hawk, whose name is also connected to Nisqually. Son James McAllister, Jr. returned to Kentucky where he married a cousin, Belle McAllister. In 1882 he moved to Grays Harbor County, then to Yakima and ultimately to Orting where he died of a stroke. He lies here near his parents. |

|||||||||

| A.

Benton Moses and Joseph Miles at Connell's

Prairie Submitted

by Gary Reese

From usgennet.org |

|||||||||

| "Obituary,

A. Benton Moses" Pioneer and Democrat,

November 2, 1855. On Wednesday, October 31,1855, Colonel A. Benton Moses, Aid de Camp to Captain Maurice Maloney, Colonel of the Militia District composed of Pierce and Sawamish counties and U.S. Surveyor of Customs for the Port of Nesqually, District of Puget Sound. He was born in Charleston, South Carolina. The subject of this notice is well known to the citizens of our Territory where he has resided since the fall of 1851, and during the whole of that period he has been more or less in official positions. He enlisted as a volunteer in the Mexican war, and served with credit on both the lines of General Taylor and Scott and was promoted to a 1st Lieutenancy. He served creditably under Lt. Colonel, now U.S. Senator Weller, in the battle of Monterey; then in the fight at Marin, and afterwards on the other lines as Aid de camp to Brig. General Childs, U.S.A. by whom he was highly esteemed. He came to California in 1849 and while there went on an expedition to Southern California against the Indians; and on his return to San Francisco was a Deputy to Colonel Jack Hays, sheriff of San Francisco, until the fall of 1851 when he accompanied his brother, the Collector of Customs to Olympia, then Oregon. That winter he was one of the volunteers to Queen Charlotte's Island to rescue the crew and passengers of the American sloop Georgiana from captivity, on that Island. He afterwards held the office of sheriff of Thurston County, which he resigned to accept the office Surveyor of Nesqually. He leaves a young widow, a mother, sisters to mourn his untimely sudden end, and a numerous circle of friends. He was so generally known in this community, that it is needless to give his characteristics. We may say that the regret at his loss, too well betokens the regard of the many friends his frank, manly and generous nature secured for him. At the same time, and in the same treacherous surprise on the part of a greatly larger force, Joseph Miles, Esq. a member of Capt. Hays company of Puget Sound Mounted Volunteers, met his fate, by a bullet shot through his neck, his body being found by Major Tidd some fifteen paces from the spot where he had been seen alive. At the time of his death, he held the office of Lieutenant Colonel of the Militia of Thurston County and Justice of the Peace of Olympia, to both which offices he had been elected by large majorities at the late general election. Lt. Col. Miles had lived in Olympia very nearly two years, and was among the first to respond to the call of the Executive for volunteers. At that time he with his brother, was engaged in the erection of the Capitol. He was a good citizen and a useful man in our community, and leaves a large circle of acquaintances and friends to mourn his untimely loss. To his brother, and his family at home we extend the assurance of our sympathy in this bereavement. We can but remind them in these melancholy occurrences, what tradition and education so potently teach us all, that death in our country's service is holy martyrdom, that there is no holier appeal to man's sympathies and regard, than to pursue as our guide star that beautiful precept: "Stand firm for your country, and become a man, Honor'd and lov'd: It were a noble life, To be found dead embracing her." A. BENTON MOSES. "Pioneer reminiscences of Mrs. John G. Parker," Early History of Thurston County, Washington. compiled and edited by Mrs. George E. Blankenship. Olympia, Washington, 1914. p. 95-106. "My cousin Sarah by this time was married to young A. Benton Moses and was living in Olympia also. When the Indian war broke out Mr. Moses was one of the first white men to lose his life by the Indians. He was killed out on Connells Prairie while in company with a small body of men who were going to join the volunteers. The others were obliged to flee for their own lives and leave the poor Tad there on the prairie.

"He was wounded but not killed outright. When he fell from his horse he begged his companions to save themselves and sent a loving message to his young girl bride. A few days later Tom Prather and a small company of men went out and brought the body back to Olympia. "Never will I forget the tragedy of that funeral. Besides Mr. Moses there were the bodies of Lieutenant McAllister and Col. Miles, who were also killed at the same time. These bodies, placed in rude coffins, were placed in one of the two wagons in the settlement. In the other wagon rode Sarah, Mrs. Cock and myself, the men walking in a procession behind the wagons. "Our wagon Was without springs of any kind and such as are used to haul dirt in. There were no seats and only some boards laid across the bed. Several times these boards slipped off arid let the mourners down in the bottom of the wagon bed. "The day was dark and dreary and the road but little more than a rough trail. It was a terrible experience. To do honor to the brave boys who had lost their lives in the attempt to protect others, the citizens decided that a military funeral was proper, so music must be included. This consisted of a drum and fife. As we wended our way out to the graveyard over and over again did this drum and fife sound out the strains of, `The Girl I Left Behind Me.' That was the only tune they could play and they did the best they could, but I thought Sarah's heart would surely break. The graveyard was the one out on the road leading to what is now Little Rock, near Belmore. Here the three graves were made close to the road, side by side. And here soon after was laid the remains of Charles H. Mason, the first Secretary of the Territory, a gallant young man of good family, who died of fever when only 29 years of age. I think the Thurston County Historical Society could do no better work than mark the last resting place of these heroes of the Indian war. |

|||||||||

McAllister home. Yakima

Herald April 26, 2015

|

|||||||||

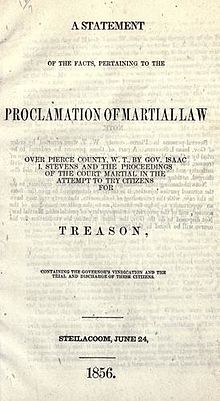

| Indian Wars EARLY HISTORY OF THURSTON COUNTY, By Mrs. George E. Blankenship, 1914 "The people were disappointed in receiving arms that were expected at that time, which necessitated a visit by Surveyor General Tilton to Seattle with a view to securing arms from the Decatur, a sloop of war, and the revenue cutter Jefferson Davis, both then in the harbor. He was successful to the extent of securing 30 muskets, 40 carbines, 50 holster pistols, 50 sabers and belts and 3500 ball cartridges. Nathan Eaton, a settler in Thurston, was authorized by Acting Governor Mason, to organize a Company of Rangers which was officered as follows: First Lieutenant, James McAllister ; Second Lieutenant, James Tullis ; Third Lieutenant. A. M. Poe ; First Sergeant, John Harold ; Second Sergeant, Chas. E. Weed ; Third Sergeant, W. W. Miller ; Fourth Sergeant, S. Phillips ; First Corporal, S. D. Reinhart ; Second Corporal, Thos. Bracken ; Third Corporal, S. Hodgdon ; Fourth Corporal, James Hughes. Both Companies proceeded to White River valley on October 20, 1855. A Company was organized on Mound Prairie and the citizens then built a blockhouse for protection. A Company was also formed on Chambers Prairie. As a precautionary measure it was deemed wise to hold a reserve force and four more Companies were called for. By the terms of this call, Lewis, Thurston, Pierce and Sammamish were to furnish one Company to enroll at Olympia. This Company enrolled 110 men and elected the following officers: Captain, Geo. B. Goudy; First Lieutenant, W. B. Affleck; Second Lieutenant, J. K. Hurd; First Sergeant, Francis Lindler; Second Sergeant, A. J. Baldwin; Third Sergeant, F. W. Sealy; Fourth Sergeant, James Roberts. Jos. Walraven, E. W. Austin, Hiel Barnes and Joseph Dean, Corporals. Stockades for the protection of families were built in this County, one on Chambers Prairie and one on Mound Prairie. Business was practically suspended in town and claims were abandoned in the country. Men were either pre- paring to leave for the scene of the trouble or were engaged in the erection of forts and stockades for protection. The Rangers left home on October 24th, to seek the wilv Chief of the Nesquallys, Leschi, who was the instigator of much of the trouble and hostile attitude of many of the natives, but they found he had gone to the White River Valley, and the troops immediately started in pursuit. At Puyallup Crossing, Captain Eaton, Lieutenant McAllister and Connell, together with a friendly Indian, went ahead of their Company to have a conference with the Indians. The Indians, with characteristic treachery, professed friendship. Upon returning to camp, McAllister and Connell were fired upon and killed. An Indian rode to the McAllister claim and told the family of McAllister's death and helped them to the fort on Chambers' Prairie. A few days later Cols. A. B. Moses and Joseph Miles were killed. It was for the murder of these men that Leschi was afterward executed. Emissaries from the hostiles on the East side of the mountains visited the Sound Indians, and by ingenious argument incited the natives on this side to hostility. Straggling bands were perpetrating outrages here and there, and thus were families intimidated and forced to take refuge in Olympia. A town meeting was held, at which Wm. Cock was chosen chairman and Elwood Evans, secretary. After discussing the situation it was resolved to build a stockade. Rev. J. F. Devore, R. M. Walker and Wm. Cock were constituted a committee to proceed at once on works for defense, and, if necessary, to detain the brig Tarquina, then in the harbor, as a means of refuge. While this condition existed and a sable cloud lay low over the little town, the bodies of McAllister, Moses and Miles were brought in, and during a dismal fall of rain, the little community bared their heads in grief over the mortal remains of their first martyrs. The three young men were buried on Chambers' Prairie. ??? A stockade was erected along Fourth Street, from bay to bay, with a block house at the corner of Main, on which was placed a cannon. These were merely precautionary measures. Actual fighting occurred only in the White and Puyallup Valleys, and in December, the Militia Companies were disbanded. An attack on Seattle occurred January 26, 1856, and Governor Stevens then issued a proclamation calling for six Companies, two of which were to enroll at Olympia. The entire white population of the Sound at this time was barely 4,000 souls and all the male population fit to bear arms had been and were now devoting their time and energies to defense, rather than in the pursuit of their occupations ; they were destitute and discouraged, and were receiving little or no help from the Government. The first Company here to respond was officered as follows : Captain, Gilmore Hays ; First Lieutenant, A. B. Rabbeson ; Second Lieutenant, Wm. Martin; Orderly Sergeant, Frank Ruth ; Sergeants, A. J. Moses, D. , Martin, M. Goddell ; Corporals, N. B. Coffey, J. L. Myers, F. Hughes, H. Horton. A Company of Mounted Rangers elected officers as follows : Captain, B. L. Henness ; First Lieutenant, Geo. C. Blankenship; Second Lieutenant, F. A. Godwin; Sergeants, Jos. Cushman, W. J. Yeager, Henry Laws, Jas. Phillips ; Corporals, Wni. E. ICady, Thos. Hicks, S. A. Phillips, H. A. Johnson. On February 8 there was organized a company of miners and sappers under Captain Jas. A. White ; U. E. Hicks, First Lieutenant ; McLain Chambers, Second Lieutenant ; D. J. Hubbard, C. White. Marcus McMillan, H. G. Parsons, Sergeants, Corporals, Isaac Lemon, Wm. Ruddell, Wm. Mengle. This Company was organized to cut roads, build fortifications, guard stock, etc. Adjutant General Tilton, on March 1, issued a call for 100 more men for service under Major Hays, with headquarters at Olympia, and in April a block house was built, sufficient to accommodate the whole population, on a site now known as Capital Park. The spot is indicated by a stone, erected by the Daughters of the American Revolution, to mark the end of the Oregon trail. The Indians now seemed tiring of the unavailing struggle, although a Peace Commission composed of M. T. Simmons and Ed. C. Fitzhugh, appointed by the Governor to treat with the Indians, was unable to bring about satisfactory results. But the Indians were disbanding and the soldiers returned home, subject to call and were finally mustered out in August. The horses, stores, etc., were sold at public auction. An incident which shows the characteristic integrity and regard for honor prevalent among the pioneers is here given. An officer of one of the volunteer Companies had captured a mule in Grand Ronde Valley. While in the service, he rode it home to Olympia, and turned it in. He desired to bid it in and own it, but the highest bid was $475 and the faithful volunteer, impoverished by ten months' military service, was unable to meet the raise. During the struggle stockades and block houses had been built in Thurston County by settlers as follows : Stockade at Cochran's, Skookumchuck; stockade. Fort Henness, Grand Mound Prairie; stockade at Goodells, Grand Mound Prairie; block house, Tenalquct Prairie; block house. Nathan Eaton's. Chambers Prairie; two block houses. Chambers Prairie; block liouse at Ruddell's. Chambers Prairie; stockade at Bush's. Bush Prairie; block house at Rutledge's. Bush Prairie; two hlock houses in Tumwater; block house at Doffelmeyer's Point. Forts and block houses built in Thurston County by the Volunteers were : Block house at Skookumchuck, Fort Miller. Tenalquot Plains; Fort Stevens, Yelm Prairie; block house at Lowe's, Chambers Prairie; block house and stockade at Olympia. No stockades were built by the Federal troops in Thurston County. The Volunteers had acquitted themselves creditably. Though a sturdy type of the Western pioneer, they had subjected themselves to strict discipline. All captured property was turned over or accounted for. No case of wanton killing of Indians had been reported. At the close of hostility the settlers justly felt that the murderers among the Indians should be tried and subjected to punishment. In this they were firmly supported by Governor Stevens. In a letter to Col. Casey, the Governor asked his assistance to this end : "I have, therefore, to request your aid in apprehending Leschi, Qui-ee-muth. Kitsap, Slahi and Nelson, and other murderers, and to keep them in custody awaiting a warrant from the nearest magistrate. "In conclusion I have to state that I do not believe that any country or any age has afforded an example of the kindness and justice which has been shown towards the Indians by the suffering inhabitants of the Sound during the recent troubles. They have, in spite of the few cases of murder which have occurred, shown themselves eminently law-abiding, a just and forbearing people. They desire the murderers of the In- dians to be punished, but they complain, and they have a right to complain, if the Indians, whose hands are steeped in the blood of the innocent, go unwhipped of justice." There had arisen a question between the Governor and the military as to whether any promise of protection had been made to the Indians when they delivered themselves up to Colonel Wright iii Yakima, Col. Casey claiming that to attempt to hold any on a charge of murder would be a violation of good faith. The Governor positively controverted the assumption of protection to the Indians, as he had received positive assurance from Col. Wright that he had made no terms with them and promised them no immunity. The Governor, relying upon this statement made to him by Col. Wright, in the presence of creditable witnesses, refused to receive and take charge of a party of about 100 Sound Indians until the murderers' were arrested, claiming that Lesehi and the others had committed murders in time of peace, in a barbarous way, when their victims were unaware of danger. However, the accused murderers were arrested and indicted and received by Col. Casey for custody at Fort Steilacoom, whereupon the Governor took charge of the other Indians and returned them to their reservations. At the first trial of Lesehi the jury disagreed, but at a subsequent trial he was convicted. The case was appealed to the Supreme Court, where the judgment of the lower court was affirmed, and the murderer was sentenced to be hanged on January 22, 1858, at Fort Steilacoorm. Petitions were circulated for pardon and numerous remonstrances were filed with the Governor, but the Governor declined to interfere. Time for the execution passed and Lesehi still lived. A committee, appointed by indignant citizens, inquired into the cause for delay. The report of this committee disclosed interference by the military authorities at Fort Steilacoom, and severely censured the Sheriff of Pierce County. At a session of the Supreme Court February 12, 1858, Lesehi was re-sentenced to hang February 19. Sheriff Hays was ordered to carry out the order of the court. In the absence of the Sheriff. Deputy Mitchell went, with a posse of twelve men, to Steilacoom, where the sentence was carried out and Leschi was made to pay the penalty of his crimes. Yelm Jim, who had been charged with the murder of Wm. White in March, 1856, came to trial April, 1859. He was found guilty and was sentenced to be hanged. Before the time set for the execution arrived, however, two Indians came to Olympia and confessed to the crime. Yelm Jim was pardoned. Qui-ee-muth, Leschi's brother, was captured near Yelm and brought to the Governor's office in Olympia late at night. The Governor stationed a guard over the Indian, with strico orders for protection until morning, when the prisoner would be removed to Steilacoom. About daylight, while the guard slept, a man burst into the room, shooting the Indian in the arm and then stabbing him. The deed was done and the assassin gone before the guard was thoroughly aroused. The man making the attack was not identified, and no testimony could be found against anyone. The impression gained credence, however, that Joseph Bunting, son-in-law of McAllister, committed the deed, thus revenging the death of McAllister. As has been before stated, the Indians, in their hostilities toward the settlers, were much encouraged by the Hudson Bay Company. During the war there lived in the country back of Steilacoom, a number of ex-employees of the Company, who had Indian wives and half breed children. It was reported to the Governor that these men were giving aid and comfort to the Indians. The Indians who killed White and Northcraft in Thurston County, were tracked straight to the houses of these men, who, when asked concerning it, admitted the fact, but denied any knowledge of their acts. As a precautionary measure, the Governor ordered these men to remove either to Steilacoom, Nisqually or Olympia, until the end of hostilities, where they would be harmless to the interests of the settlers. Accordingly twelve of them moved in. They had taken out their first papers and had located donation claims. A few lawyers who had not distinguished themselves by assisting, or even been identified with, the worthy settler in resisting the Indians, here saw a chance for serving their own purposes, and incited these men to resist the Governor's order in the courts, and in the mean- time return to their claims, which five of them did. On learning this, the Governor ordered them arrested and turned over to Col. Casey at Fort Steilacoom. Then the designing lawyers sued out a writ of habeas corpus. To forestall an effort on the part of the conspirators to seriously impair the plans of his administration, the Governor declared martial law on April 3. The prisoners were brought to Olympia and incarcerated in the old block house on the public square. Judge Chenoweth, whose place it was to hear the proceedings, plead illness, and asked Judge Lander, whose district included Thurston County, to hear the habeas corpus cases. Lander hastened to Steilacoom and opened court May 7. The Governor had urged the Judge to adjourn court until Indian troubles were over, which must necessarily be soon, and all trouble thus averted. But Lander proceeded to open court, whereupon Col. Shaw walked into court and arrested the Judge and the officers of his court and brought them to Olympia, where they were released. Lander, being then at home, and the time for holding court in his own district having arrived, he opened court on the 14th, and summoned the Governor to answer contempt proceedings. The Governor ignored the order and accordingly United States Marshal Geo. W. Corliss proceeded to the Governor's office to arrest him. The Marshal and his party, however, after failing to execute their errand, were ejected from the office by a party composed of Major Tilton, Capt. Cain, Jas. Doty, Q. A. Brooks, R. M. Walker, A. J. Baldwin, Lewis Ensign, Chas. E. Weed and J. L. Mitchell. Mounted volunteers entered the Town and Judge Lander hearing of their approach, adjourned court, and, in company with Elwood Evans, went to the office of the latter and locked themselves in. Captain Miller, with his men, approached, and finding himself barred, remarked: "I will here add a new letter to the alphabet, let 'er rip," and kicked in the door and arrested the occupants of the room. Evans was released at once. Lander was held in honorable custody until the war was over. Much was made of this act by the enemies of Governor Stevens to injure him and his administration. A mass meeting was held in Olympia on the public square (now Capital Park), which was presided over by Judge B. F. Yantis, J. W. Goodell, Secretary, which heartily endorsed the course of the Governor in declaring martial law. The proclamation revoking martial law was promulgated May 24 and Lander held court in July following. The Governor appeared in court by counsel disclaiming any disrespect to the Court, was fined $50, which he paid, and the incident was closed. |

|||||||||

| HISTORY OF OLYMPIA MASONIC LODGE No. 1, F. & A. M. OLYMPIA, WASHINGTON 1852 – 1935 George E. Blankenship, Compiler ...A particularly noticeable feature of the proceedings of early meetings is the discipline maintained. These pioneer Masons were ritualists as far as their limited facilities permitted, but what was more commendable they were sticklers for what the ritual stood for, and frowned with puritanic severity upon hypocrisy. Those members who stepped beyond the bounds of propriety and violated Masonic teachings were haled before the bar and disciplined. A notable instance was that of James McAllister, a member of No. 5, who, while hunting cattle, killed two steers belonging to members of Steilacoom Lodge. Mr. McAllister, on discovering his mistake, went to the owners and offered to make a settlement, but the owners of the cattle were exorbitant in their demands, whereupon the two Lodges took the matter in hand and forced a settlement. No lawyers were feed nor courts called upon, but the settlement was effectual. Cases of intemperance were dealt with with patience and firmness, and one member who was known to frequent gambling places was hailed for judgment. His case was set for six months in advance, a probationary period in which to test the sincerity of his promise of reform. Two brothers who engaged in wordy conflict on the street were reprimanded, and a member leaving town without paying his creditors was expelled. In later years we have erected magnificent temples in the name of Masonry, but they will mock high Heaven if they do not demonstrate the teachings of the Fraternity as exemplified by our predecessors. The incidents cited above were taken at random from the minutes to show how our antecedents lived their Masonry and set an example that Masons of today may well profit by. Masonry then meant more than commercial or political advantage and an emblem. The pioneer had a tear for pity and a hand open as the day for meeting charity, but he was an austere mentor. May 7, 1859, the Lodge took steps toward building a sidewalk to connect with the town, which, when completed, was a boon for the juvenile population of the village who utilized it as a coasting course, furnishing a good steep grade from the hall to the old blockhouse, which stood where is now the marker for the end of the Oregon Trail. There was much privation endured in those days, in everyday life, but there was some recompense. There is a notable contrast in comparison with the hold-up methods of today. No. 1 paid a bill for $33.78 for its Lodge room furniture; $1.12 per yard for its carpet, and it was a good carpet for it endured for years; 6 chairs for $9.00. These chairs were durable, for they are today in the hands of members of No. 1, who purchased them when the old hall was dismantled. It costs a great deal to live in these effete days of the automobile and enervating luxury, but it costs more to die. Now when one proposes to draw the draperies of his couch about him and lie down to pleasant dreams, he must leave an estate of at least $1,000.00 for funeral expenses or the obsequies will not be attended by the elect, while in 1850 to 1860 one could light out for that bourne from whence no traveler returns for about $36.00, as the record shows, and make a pretty good appearance at that. The necessary offices were performed by surviving brothers without price, and the deceased was taken out south of town in a dead-ex wagon rather than a gasoline hearse, but no one of the deceased was ever heard to complain about his conveyance. One of the first funerals at which Olympia Lodge presided was one somewhat historic in the annals of the territory. The services were held over the remains of A. Benton Moses, of Steilacoom Lodge, and Joseph Miles. Moses and Miles had been shot from ambush by the Indians near Connell prairie, while in company with a small body of volunteers who were going to join the main body. These Indians were instigated in the murder by Chief Leschi, who was tried for the crime and eventually hung. Leschi was a fit subject for the hangman’s noose then. Today, thanks to Ezra Meeker, he is a hero and a martyr. There was a tragedy in the funeral. The bodies were placed in one of the two wagons in the little settlement. In the other rode the bride of six months of Mr. Moses. The day was dark and dreary and the road almost impassible. To do honor to the men who had given up their lives to protect others, the citizens demanded a military funeral, and, as such, music was indispensable. The band consisted of a fife and drum. As the procession wended its way to the graveyard on the road leading to what is now Little Rock, near Belmore, over and over again the band played the strains of the “Girl I Left Behind Me.” This may have a ludicrous aspect now, but it was agony for a girl who was following a young husband to his last resting place. The people were simply doing the best they could to honor these Masons with the limited means at their command. But the old order gives way for the new. Olympia Lodge is now a flourishing organization of over four hundred members, holding the proud title of No. 1 in a great jurisdiction. Harmony Lodge No. 18 was organized in 1871 and is a prosperous body of about one hundred sixty-five members. The necessities of these Lodges and the higher bodies demanded a better and a more commodious home and the old gave way for the building now occupied. Much credit is due to a committee composed of Frank Blakeslee, Chas. E. Claypool, and Robert Doragh, to whom was delegated the authority for financing and supervising the building. The corner stone for this temple was laid in 1911. In such reverence was the old building held that many were loathe to have it destroyed. In the hope of preserving it, the Grand Lodge of Washington was offered a deed to the hall and the ground upon which it stood for use as a headquarters for the Grand Lodge archives and office of the Grand Secretary. But Tacoma influence was too strong, and brought about a removal of the office of Grand Secretary to the City of Destiny, after having been maintained here since the organization of the Grand Lodge. Much of this time Thomas Milburne Reed was Grand Secretary, a man who lived his Masonry and died a sincere and consistent Christian. His memory is cherished by all who were fortunate in having his acquaintance and friendship. In such deep veneration was the old hall held that there were those in the membership of No. 1 that fought to the bitter end to save the old edifice. At last, the sentimental members offered to consent to the desecration on condition that a small lodge room would be included in the new building which would be a replica of the old Lodge room with its arch ceiling and starry embellishments. And the historic old building was razed, and an old door, the main entrance, was thrown into an abandoned barn and forgotten. The old order became a memory, with nothing to connect with the beginning of things except an old minute book and charter. By merest accident, the old door was found and rejuvenated, and upon its surface on each panel is emblazoned the high lights of northwest Masonic history. The old door was home again and hung in the old Lodge room, and its return was celebrated by a special session of No. 1, when it was installed. The old hand rail was found that had guided the Masons of old up the stairs. It was made of a hard, not a native, wood, brought from an eastern state. When the old building was razed, a thorough search failed to reveal the old corner stone laid in 1854. The door has been assigned a position in the smaller Lodge room, which in most respects is the one which it guarded, near the senior warden’s station in the west. It was the only place in the temple where wall space sufficient for its size could be found. There it will remain and as the years go by, additional history will be written upon its panels and stiles and thus through the generations will preserve, unimpaired, the history of the first Lodge in the state. The original place of meeting of Olympia No. 5, was on Second Street, between Main Street (now Capitol Way) and Washington Street, in a two-story wooden building with an outside stairway. This was also the building in which was organized the Grand Lodge of Washington. The site is now marked by a plaque on which is inscribed:

This location is a memorable one in the history of the state. In this block was held the first session of the territorial legislature in 1854. This site is also marked by a plaque installed by the Pioneer Society of the State. Here also stood an old hotel in which was held the official reception of Governor Isaac I. Stevens on his arrival in Olympia. The governor was accompanied by a party of engineers sent out by the government to locate a feasible route for a transcontinental railroad. They established their office in the block opposite. In fact, all of the little village of Olympia, made the capitol, by proclamation of Governor Stevens, of a vast domain extending from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean and from the Columbia River to the British line, was located well down toward the waterfront, but the Masons built their first Lodge hall six blocks above, well surrounded by timber. Members in good standing enrolled during 1853 and 1854 were: T.F. McElroy, J.W. Wiley, M.T. Simmons, N. Delin, Ira Ward, C.H. Hale, Smith Hays, F.A. Clark, I.B. Powers, B.F. Yantis, B.F. Shaw, J.R. Johnson, John M. Hayden, Edmund Sylvester, Courtland Etheridge, Levi M. Ford, T.W. Glasgow. These were indeed the pioneer Masons of No. 1 that participated in the laying of the corner stone of the old building June 24, 1854. At 11 o’clock on that day a procession was formed and proceeded to the site of the new Lodge building, at which time and place the corner stone was laid with appropriate ceremonies, after which the procession moved to Brother Cock’s hall at the Pacific house, as stated by the minutes, and listened to an eloquent address by J.P. Anderson on Masonry. Evidently the pioneer had the same weakness as the more modern Mason, for the minutes further state that the brethren partook of a sumptuous entertainment prepared by Brother Cock for the occasion. The Pacific house, referred to, stood on the now vacant lot opposite the city hall. Brother Cock was later suspended for insubordination and finally expelled by order of the Grand Lodge. At a meeting on August 4, a proposition to reduce the fees for the three degrees to $30.00 was discussed and rejected, the fees remaining at $50.00 The approaching Indian war had commenced, making inroads on the members of the Masonic Fraternity. As already stated, A. Benton Moses had been accorded a Masonic funeral by No. 5, and at the meeting held November 3, 1855, resolutions were passed deploring the death of A.J. Bolon. He was an Indian agent and was proceeding toward The Dalles accompanied by three Indians. One of the Indians on the trail dropped behind Bolon and shot him in the back. With the help of his companions, the murderer then cut Bolon’s throat, killed his horse, built a fire and burned the bodies of horse and man. This murderer was duly punished. His name was Kwalchen. One day he rode into Colonel Wright’s camp. The Colonel made this report of the affair, “He rode into my camp at 9 o’clock this morning and at 9:15 he was hung.” At the meeting held November 11, 1855, resolutions of regret were adopted on the death of Brother James McAllister, killed by the Indians in White River Valley. His body was found two days after the killing of Moses, before mentioned, shockingly mutilated. It may be stated in passing that the pioneer Masons spared neither space nor effort in expressing their sympathy. The resolutions commemorating the death of McAllister covered two pages of the minute book, closely written, closing with the following: “Resolved that a blank page be left in the record book of the Lodge and the name of our deceased brother be inscribed in the center thereof, with marginal black lines.” The secretary left two blank pages in the record book, but to this day they remain blank. On December 8, 1855, a communication was read from Steilacoom Lodge announcing the death of Lieutenant Slaughter. He was killed by the Indians near White River. He had been a visitor to Olympia No. 5, though a member in Steilacoom, and Olympia was asked to participate in the funeral ceremonies. Lieutenant Slaughter was a West Point graduate and assigned to the 4th Infantry, to which Lieutenant Grant (later General Grant) was assigned. He was ordered to the West and was seasick every day of his trip here. On his arrival here he was ordered to return East, on account of a mistake in his assignment. Again he suffered from seasickness and, when Grant found him in Panama in 1852, still sick, he told his superior that he wished he had joined the Navy, for then he probably would not have to go to sea so much. Closely interwoven with the early history of Washington is that of Masonry, for the outstanding characters that were bearing the burdens of pioneer life and carrying on contests with the Indians were Masons. At a meeting on February 7, 1857, a resolution was passed urging the granting of a petition for the establishment of a Lodge of Masons at Grand Mound. The petitioners were: Charles Byles, James Byles, I. Axtell, W.B.D. Newman, C.E. Baker, B.C. Armstrong, Aaron Webster, B.F. Yantis, and R.S. Doyle. The petition was granted, and the Lodge survived for a few years. The meeting of September 19, 1857, was notable for several distinguishing features. Among the visitors notes was Fayette McMullen of Catlett Lodge No 35, Virginia. This gentleman was the second governor of the territory. Selucius Garfield and W.W. Miller were balloted on and elected. Garfield was later to represent the territory in congress, and W.W. Miller was Adjutant General during the troublous Indian war times. Thomas M. Reed, of Acacia Lodge No. 92, appeared as a visitor on January 16, 1858. This brother was destined to be a very prominent figure in future Masonic history. He affiliated here on June 5, 1858. The first move toward selection of a Masonic cemetery was made on March 6, 1858, when a committee reported progress on the matter. The Lodge later accepted the donation of a tract of land made by Smith Hays, stipulating that the land was a donation on consideration of the Lodge’s clearing and cultivating the three acres given. On September 4, 1858, a contract was approved for clearing the cemetery ground." |

|||||||||

| THE

YAKIMA WAR The Yakima War (1855-1858) was a conflict between the United States and the Yakama, a Sahaptian-speaking people of the Northwest Plateau, then part of Washington Territory, and the tribal allies of each. It primarily took place in the southern interior of present-day Washington, with isolated battles in western Washington and the northern Inland Empire sometimes separately referred to as the Puget Sound War and the Palouse War, respectively. This conflict is also referred to as the Yakima Native American War of 1855. BackgroundTreaties between the United States and several Indian tribes in the Washington Territory resulted in reluctant tribal recognition of U.S. sovereignty over a vast amount of land in the Washington Territory. The tribes, in return for this recognition, were to receive half of the fish in the territory in perpetuity, awards of money and provisions, and reserved landswhere white settlement would be prohibited. While governor Isaac Stevens had guaranteed the inviolability of Native American territory following tribal accession to the treaties, he lacked the legal authority to enforce it pending ratification of the agreements by the United States Senate. Meanwhile, the widely-publicized discovery of gold in Yakama territory prompted an influx of unruly prospectors who traveled, unchecked, across the newly defined tribal lands, to the growing consternation of Indian leaders. In 1855 two of these prospectors were killed by Qualchin, the nephew of Kamiakin, after it was discovered they'd raped a Yakama woman.[1] Outbreak of hostilitiesDeath of Andrew BolonOn September 20, 1855, Bureau of Indian Affairs agent Andrew Bolon, hearing of the death of the prospectors at the hands of Qualchin, departed for the scene on horseback to investigate but was intercepted by the Yakama chief Shumaway who warned him Qualchin was too dangerous to confront. Heeding Shumaway's warning, Bolon turned back and began the ride home. En route he came upon a group of Yakama traveling south and decided to ride along with them. One of the members of this group was Mosheel, Shumaway's son.[2] Mosheel decided to kill Bolon for reasons that are not entirely clear. Though a number of Yakama in the traveling party protested, their objections were overruled by Mosheel who invoked his regal status. Discussions about Bolon's fate took place over much of the day (Bolon, who did not speak Yakama, was unaware of the conspiracy unfolding among his traveling companions). During a rest stop, as Bolon and the Yakama were eating lunch, Mosheel and at least three other Yakama set upon him with knives. Bolon yelled out in a Chinook dialect, "I did not come to fight you!" before being stabbed in the throat.[3] Bolon's horse was then shot, and his body and personal effects burned.[4] Battle of Toppenish CreekWhen Shumaway heard of Bolon's death he immediately sent an ambassador to inform the U.S. Army garrison at Fort Dalles, before calling for the arrest of his son, Mosheel, who he said should be turned-over to the territorial government to forestall the American retaliation he felt would likely occur. A Yakama council overruled the chief, however, siding with Shumaway's older brother, Kamiakin, who called for war preparations. Meanwhile, district commander Gabriel Rains had received Shumaway's ambassador and, in response to the news of Bolon's death, ordered Major Granville O. Haller to move out with an expeditionary column from Fort Dalles. Haller's force was met and turned-back at the edge of Yakama territory by a large group of Yakama warriors. As Haller withdrew, his company was engaged and routed by the Yakama at the Battle of Toppenish Creek.[5] War spreadsThe death of Bolon, and the United States defeat at Toppenish Creek, caused panic across the territory with fears that an Indian uprising was in progress. The same news, however, emboldened the Yakama and uncommitted bands rallied to Kamiakin. Rains, who had just 350 federal troops under his immediate command, urgently appealed to Acting Governor Charles Mason (Isaac Stevens was still returning from Washington, D.C. where he had traveled to present the treaties to the Senate for ratification) for military aid, writing that,[6]

Meanwhile, Oregon Governor George Law Curry mobilized a cavalry regiment of 800 men, a portion of which crossed into Washington territory in early November.[7] Now with more than 700 troops at his disposal, Rains prepared to march on Kamiakin who had encamped at Union Gap with 300 warriors.[5] Raid on the White River settlementsAs Rains was mustering his forces, in Pierce County, Leschi, a Nisqually chief who was half Yakama, had sought to forge an alliance among the Puget Sound tribes to bring war to the doorstep of the territorial government. Starting with just the 31 warriors in his own band, Leschi rallied more than 150 Muckleshoot, Puyallup, and Klickitat though other tribes rebuffed Leschi's overtures. In response to news of Leschi's growing army, a volunteer troop of 18 dragoons, known as Eaton's Rangers, was dispatched to arrest the Nisqually chief.[8] On October 27, while surveying an area of the White River, ranger James McAllister and farmer Michael Connell were ambushed and killed by Leschi's men. The rest of Eaton's Rangers were besieged inside an abandoned cabin, where they would remain for the next four days before escaping. The next morning Muckleshoot, and Klickitat warriors raided three settler cabins along the White River, killing nine men and women. Many settlers had left the area in advance of the raid, having been warned of danger by Chief Kitsap of the neutral Suquamish. Details of the raid on the White River settlements were told by John King, one of the four survivors, who was seven years old at the time and was - along with two younger siblings - spared by the attackers and told to head west. The King children eventually came upon a local Native American known to them as Tom.[8]

Leschi would later express regret for the raid on the White River settlements and post-war accounts given by Nisqually in his band affirmed that the chief had rebuked his commanders who had organized the attack.[9] Battle of White RiverArmy Captain Maurice Maloney, in command of a reinforced company of 243 men, had previously been sent east to cross the Naches Pass and enter the Yakama homeland from the rear. Finding the pass blocked with snow he began returning west in the days following the raid on the White River settlements. On November 2, 1855 Leschi's men were spotted by the vanguard of Maloney's returning column, and fell back to the right bank of the White River.[8] On November 3 Maloney ordered a force of 100 men under Lt. William Slaughter to cross the White River and engage Leschi's forces. Attempts to ford the river, however, were stopped by the fire of Indian sharpshooters. One American soldier was killed in a back-and-forth exchange of gunfire. Accounts of Indian fatalities range from one (reported by a Puyallup Indian, Tyee Dick, after the end of the war) to 30 (claimed in Slaughter's official report), though the lower number may be more credible (one veteran of the battle, Daniel Mounts, would later be appointed Indian agent to the Nisqually and heard Tyee Dick's casualty numbers confirmed by Nisqually). At four o'clock, when it was becoming too dark for the Americans to cross the White River, Leschi's men fell back three miles to their camp on the banks of the Green River, jubilant at having successfully prevented the American crossing (Tyee Dick would later describe the battle as hi-ue he-he, hi-ue he-he - "lots and lots of fun").[8] The next morning Maloney advanced with 150 men across the White River and attempted to engage Leschi at his camp at the Green River, but poor terrain made the advance untenable and he quickly called off the attack. Another skirmish on November 5 resulted in five American fatalities, but no Indian deaths. Unable to make any headway, Maloney began his withdrawal from the area on November 7, arriving at Fort Steilacoom two days later.[8] Battle of Union GapOne hundred fifty miles to the east, on November 9, Rains closed with Kamiakin near Union Gap.[10] The Yakama had erected a defensive barrier of stone breastwork which was quickly blown away by American artillery fire. Kamiakan had not expected a force of the size Rains had mustered and the Yakama, anticipating a quick victory of the kind they had recently scored at Toppenish Creek, had brought their families. Kamiakan now ordered the women and children to flee as he and the warriors fought a delaying action. While leading a reconnaissance of the American lines, Kamiakan and a group of fifty mounted warriors encountered an American patrol which gave chase. Kamiakan and his men escaped across the Yakima River; the Americans were unable to keep up and two soldiers drowned before the pursuit was called off. That evening Kamiakan called a war council where it was decided the Yakama would make a stand in the hills of Union Gap. Rains began advancing on the hills the next morning, his progress slowed by small groups of Yakama employing hit and run tactics to delay the American advance against the main Yakama force. At four o'clock in the afternoon Maj. Haller, backed by a howitzer bombardment, led a charge against the Yakama position. Kamiakan's forces scattered into the brush at the mouth of Ahtanum Creek and the American offensive was called off.[11] In Kamiakan's camp, plans for a night raid against the American force were drawn up but abandoned. Instead, early the next day, the Yakama continued their defensive retreat, tiring American forces who eventually broke off the engagement. In the last day of fighting the Yakama suffered their only fatality, a warrior killed by U.S. Army Indian Scout Cutmouth John.[11] Rains continued to Saint Joseph's Mission which had been abandoned, the priests having joined the Yakama in flight. During a search of the grounds, Rains men discovered a barrel of gunpowder, leading them to erroneously believe the priests had been secretly arming the Yakama. A riot among the soldiers ensued and the mission was burned to the ground. With snow beginning to fall, Rains ordered a withdrawal, and the column returned to Fort Dalles.[7] Skirmish at Brannan's PrairieBy the end of November, federal troops had returned to the White River area. A detachment of the 4th Infantry Regiment, under Lt. Slaughter, accompanied by militia under Capt. Gilmore Hays, searched the area from which Maloney had previously withdrawn and engaged Nisqually and Klickitat warriors at Biting's Prairie on November 25, 1855, resulting in several casualties but no decisive outcome. The next day an Indian sharpshooter killed two of Slaughter's troops. Finally, on December 3, as Slaughter and his men were camped for the night on Brannan's Prairie, the force was fired upon and Slaughter killed. News of the death of Slaughter greatly demoralized settlers in the principal towns. Slaughter and his wife were a popular young couple among the settlers and the legislature adjourned for a day of mourning.[12] Conflict of commandIn late November 1855 Gen. John E. Wool arrived from California and assumed control of the United States side in the conflict, making his headquarters at Fort Vancouver. Wool was widely considered pompous and arrogant and had been criticized by some for blaming much of the western conflicts between Natives and whites on whites. After assessing the situation in Washington, he decided that Rains' approach of chasing bands of Yakama around the territory would lead to an inevitable defeat. Wool planned to wage a static war by using the territorial militia to fortify the major settlements while better trained and equipped U.S. Army regulars moved-in to occupy traditional Indian hunting and fishing grounds, starving the Yakama into surrender.[13] To Wool's chagrin, however, Oregon Governor Curry decided to launch a preemptive and largely unprovoked attack against the eastern tribes of the Walla Walla, Palouse, Umatilla, and Cayuse who had, up to that point, remained cautiously neutral in the conflict (Curry believed it was only a matter of time before the eastern tribes entered the war and sought to gain a strategic advantage by attacking first). Oregon militia, under Lt. Col. James Kelley, crossed into the Walla Walla Valley in December, skirmishing with the tribes and, eventually, capturing Peomoxmox and several other chiefs. The eastern tribes were now firmly involved in the conflict, a state-of-affairs Wool blamed squarely on Curry. In a letter to a friend, Wool commented that,[13]